BECOME POLISH

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

DIVE INTO A LIFESTYLE

From the legacy of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth to the spiritual richness of Catholic tradition and the resilience of modern Polish identity, Poland stands as a powerful example of cultural endurance at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. Polish heritage reflects layers of Slavic, Roman, Germanic, Jewish, and Baltic influences—all woven into a distinctly Polish spirit. Combined with its dramatic geography—from the Tatra Mountains to the Masurian Lakes, and from the historic cities of Kraków and Gdańsk to the cultural heart of Warsaw—Poland offers a captivating journey through centuries of layered history and artistic achievement.

Following the partitions of the 18th century, the restoration of independence in 1918, the trauma of World War II, and the long decades of communist rule, Poland entered the 21st century with a renewed sense of purpose. Its modern transformation has been marked by resilience, innovation, and a reaffirmation of cultural identity. Today, Poland is a dynamic presence in European politics, literature, science, and the arts, drawing strength from its past while shaping its future with confidence. Polish culture continues to thrive in music, cinema, cuisine, folklore, and literature—often marked by emotional depth, philosophical reflection, and a quiet but determined intensity that resonates on the global stage.

We’ve curated a special selection of Polish words you won’t find in standard textbooks or apps—words that carry deep cultural meaning and emotional nuance. These expressions help you sound more natural, connect more deeply, and understand Polish life in all its richness—from everyday speech to untranslatable concepts that reveal how Poles see the world.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are serious about learning Polish, we recommend that you download the Complete Polish Master Course.

You will receive all the information available on the website in a convenient portable digital format as well as additional contents: over 15.000 Vocabulary Words and Useful Phrases, in-depth explanations and exercises for all Grammar Rules, exclusive articles with Cultural Insights that you won't in any other textbook so you can amaze your Polish friends or business partners thanks to your knowledge of their country.

With a one-time purchase you will also get hours of Podcasts to Practice your Polish listening skills as well as Dialogues with Exercises to achieve your own Master Certificate.

Start speaking Polish today!

ANDRZEJKI

ANDRZEJKI (St. Andrew’s Eve) is one of the most enchanting and mysterious traditions in Poland, celebrated each year on the night of November 29th. Rooted in folk belief and rural customs, Andrzejki (St. Andrew’s night) is primarily associated with wróżby (fortune-telling), especially among young women hoping to gain insight into their future, particularly regarding love and marriage. Historically, this event was only celebrated by unmarried women, while men had their equivalent on Katarzynki (St. Catherine’s Day), but over time, Andrzejki has evolved into a co-ed celebration full of fun, suspense, and superstition.

One of the most iconic wróżby andrzejkowe (Andrzejki-style predictions) involves pouring hot wosk (wax) into cold water through a keyhole or spoon with a hole, then interpreting the shape of the hardened wax as it floats on the surface. Another popular game includes buty (shoes) being placed in a line from the far wall to the door; whoever's shoe reaches the threshold first is believed to be the next to marry. These games often take place in an intimate domestic setting or as part of larger school and community events, infused with candlelight, laughter, and often eerie silence during the most serious moments. The ambience is enhanced by ciemność (darkness) and flickering świece (candles), invoking a spiritual or supernatural dimension, especially when participants seek signs in dreams or mirror reflections. Although many view these rituals with a playful or ironic eye today, the tradition remains a cherished and culturally significant night in the Polish calendar.

Andrzejki offers a rare blend of mystical folklore, communal play, and emotional introspection. In some homes, older relatives recount their own andrzejkowe historie (Andrzejki stories) or tales of dreams that came true, deepening the connection between generations and enriching the evening’s charm. Food and drink accompany the fortune-telling, with traditional snacks like pierogi (dumplings), ciasto drożdżowe (yeast cake), and sometimes even nalewka (homemade liqueur), adding to the festive mood.

Though originally a rural and religious observance, modern Andrzejki now blends old superstition with contemporary party culture, celebrated in homes, clubs, and schools across Poland. Its enduring popularity reflects not just nostalgia, but a deeply embedded cultural rhythm, where even in a world driven by science and logic, a bit of magic, mystery, and playful destiny still find their place. Whether you're pouring wax or racing shoes, Andrzejki invites everyone into a night where past, present, and future briefly mingle under the spell of folklore.

BAR MLECZNY

BAR MLECZNY (milk bar) represents one of the most distinctive and enduring institutions of Polish daily life, blending socialist-era functionality with traditional culinary heritage. Originally conceived in the early 20th century but rising to prominence during the PRL (People’s Republic of Poland) period, the bar mleczny was designed as an affordable dining option for workers, students, and pensioners, offering nutritious meals at state-subsidized prices. Despite the name, these establishments do not specialize in dairy products but rather in domowe jedzenie (home-cooked food) that reflects the core of Polish comfort cuisine. Dishes like pierogi ruskie (dumplings filled with potato and cheese), kotlet schabowy (breaded pork cutlet), zupa pomidorowa (tomato soup), and kompot (fruit compote) are staples of the bar mleczny experience.

The atmosphere is stark and utilitarian—plastic trays, laminated menus, metal cutlery—but there’s a powerful sense of authenticity and nostalgia that draws patrons across generations. Often lacking the polish of modern eateries, these bars offer an unvarnished look into everyday Polish tastes, where food is celebrated not for extravagance but for prostota (simplicity) and sytość (heartiness). There is a rhythm to the bar mleczny that is nearly sacred: line up, point to the dishes behind the counter, pay a symbolic amount, and enjoy a warm meal that tastes like it came from a Polish grandmother’s kitchen.

These establishments often carry a sense of time suspended, where the meble (furniture), obrazy (pictures), and even the obsługa (staff) seem frozen in a bygone era. For older Poles, visiting a bar mleczny recalls the days when such places were social equalizers—where factory workers, clerks, and students sat side by side over bowls of barszcz czerwony (beetroot soup). In recent decades, some feared these bars would vanish under pressure from fast food chains and rising costs, but a cultural resurgence has given them new life. The Polish state still provides subsidies to keep some of them running, viewing them as important bastions of national heritage.

Tourists are increasingly drawn to these unpretentious dining spots, eager to sample kuchnia polska (Polish cuisine) in its most genuine form. The legacy of the bar mleczny extends beyond food—it’s a symbol of resilience, community, and the enduring value of shared, accessible meals. Despite economic transformations, the bar mleczny remains a beloved part of the urban landscape in cities like Warszawa (Warsaw), Kraków (Krakow), and Gdańsk, preserving the culinary soul of Poland one spoonful at a time.

BIGOS

BIGOS (hunter’s stew) stands as one of the most iconic and deeply cherished dishes in Polish cuisine, embodying centuries of culinary tradition and national identity. Often called the król potraw (king of dishes), bigos is a robust, slow-cooked stew that brings together kapusta kiszona (sauerkraut), fresh kapusta biała (white cabbage), and a rich variety of mięso (meats)—typically including pork, wołowina (beef), kiełbasa (sausage), and sometimes game like dziczyzna (venison). The beauty of bigos lies in its complexity and depth of flavor, achieved through prolonged simmering and repeated reheating, which enhances its savory richness with each cycle. Aromatic with liść laurowy (bay leaf), ziele angielskie (allspice), grzyby suszone (dried mushrooms), and a hint of czerwone wino (red wine), this dish is not just food—it is tradycja (tradition) in a pot.

Historically, bigos was associated with the Polish nobility, served during hunting trips and grand feasts, where each family developed its own secret recipe. Over time, it became a staple in nearly every Polish household, particularly during Boże Narodzenie (Christmas) and Sylwester (New Year’s Eve), celebrated as much for its hearty taste as for its role in gathering people around the table. There is no single way to make bigos, which is part of its cultural charm—every cook adds their own touch, some incorporating śliwki suszone (dried plums), others thickening it with a bit of mąka (flour) or sweetening it with a dash of miód (honey). What remains consistent is the spirit of gospodarność (resourcefulness) it reflects, making use of leftover meats and seasonal vegetables to create a dish that warms both body and soul.

It’s not uncommon for bigos to be cooked in large batches, stored, and reheated over several days, with the flavor deepening to legendary status. In literature, bigos has been immortalized in works like Adam Mickiewicz’s Pan Tadeusz, where it is praised not just as a meal but as a patriotic symbol. To eat bigos is to taste Poland itself: smoky, sour, spicy, and earthy, a blend of peasant ingenuity and noble tradition. Whether served with chleb (bread) or enjoyed on its own, steaming hot from a pot in a mountain hut or ladled onto a plate in a Warsaw kitchen, bigos remains a culinary emblem of Polish resilience, generosity, and flavor.

BURSZTYN

BURSZTYN (amber) holds a place of profound cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance in Poland, particularly along the Baltic coast where it has been gathered, traded, and revered for millennia. Known as złoto Bałtyku (Baltic gold), bursztyn is not a gemstone in the traditional mineral sense, but fossilized tree resin that glows in hues ranging from honey and cognac to deep cherry and rare milky white. Polish amber, especially that found around Gdańsk, is among the finest in the world and has long been prized for its beauty and supposed healing properties. The Szlak Bursztynowy (Amber Route), an ancient trade path stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Mediterranean, testifies to amber’s central role in Poland’s early commercial and cultural exchanges.

Artisans in Poland, particularly in Trójmiasto (Tri-City region), continue to craft exquisite biżuteria z bursztynu (amber jewelry), rzeźby (carvings), ikony (icons), and even inlaid religious artifacts, each piece telling a story of time, nature, and craftsmanship. For many Poles, bursztyn is more than a decorative object—it’s a link to przeszłość (the past), with myths and legends surrounding its origins. Some say amber comes from the tears of the sea goddess Jurata, weeping for her lost love, while others see it as a protective stone with power to ward off złe duchy (evil spirits) or cure ailments when worn close to the skin. Small children are sometimes given naszyjniki z bursztynu (amber necklaces) believed to ease teething pain, while adults may use maści bursztynowe (amber ointments) or nalewki bursztynowe (amber tinctures) in folk medicine.

Museums in Poland, especially the Muzeum Bursztynu in Gdańsk, display ancient pieces of bursztyn z inkluzjami (amber with inclusions), where trapped insects, leaves, and air bubbles offer a preserved window into prehistoric life. During walks along the beach after storms, collectors eagerly comb the shore for raw chunks of surowy bursztyn (raw amber), often found entangled in seaweed or nestled among stones. The Polish government recognizes bursztyn as a national treasure, protected by law and celebrated through festivals, artisan fairs, and academic studies. In religious contexts, amber rosaries and crosses are used in churches, blending spiritual and material beauty.

CHABER

CHABER (cornflower) is not merely a wildflower dotting the Polish countryside—it is a powerful emblem of national identity, rural beauty, and historical memory. Known in Polish as chaber bławatek, this delicate blue flower has long been associated with the landscape of Mazowsze (Mazovia), Lubelszczyzna (Lublin region), and other vast stretches of farmland where it blooms among fields of żyto (rye) and pszenica (wheat), its vibrant petals contrasting vividly with the golden grain.

The chaber is more than aesthetically pleasing—it has served as a symbol of resilience, simplicity, and quiet defiance. During the 19th century, when Poland was partitioned and its statehood erased from maps, many Poles wore chabry (cornflowers) on their lapels or embroidered them into garments as a subtle act of patriotism, a way of saying jestem Polakiem (I am Polish) without speaking a word. In art, chabry appear in folk paintings, textile patterns, and even in traditional haft kaszubski (Kashubian embroidery), where their symmetrical shape and radiant color are rendered with precise, loving detail.

The flower also features in songs, poems, and lullabies, where it evokes innocence, homeland, and the cyclical beauty of nature. In Polish herbal traditions, chaber has long been valued for its medicinal properties—infusions made from its petals, called napar z chabra, are used to soothe the eyes or calm the nerves. As a motif, chaber is often found on ceramika ludowa (folk ceramics), obrusy haftowane (embroidered tablecloths), and even in contemporary fashion as designers seek to reconnect with motywy etniczne (ethnic motifs). In urban Poland, especially around Warszawa (Warsaw) and Kraków, cornflower-themed cafés, boutiques, and handicraft shops use the flower’s image to channel nostalgia and authenticity. The symbolic weight of chaber was formally recognized when it was chosen as a military decoration—the Order of the Cornflower—in honor of bravery and civil resistance. On commemorative occasions such as Święto Niepodległości (Independence Day), schools and cultural organizations often encourage children to craft papierowe chabry (paper cornflowers) to wear during parades or school events.

For many Poles, the chaber encapsulates what it means to be tied to the land: humble, beautiful, quietly proud. It blooms not in grand gardens but in the fields and meadows where daily life unfolds. Its presence in the Polish psyche is subtle yet firm, like a memory passed down through generations, uniting przyroda (nature), tradycja (tradition), and patriotyzm (patriotism) in a single blue blossom.

CHRZAN

CHRZAN (horseradish) is one of the most potent and enduring flavors in Polish culinary tradition, known not only for its sharp, sinus-clearing bite but also for its symbolic and ritual roles in Polish culture. A key condiment on the traditional Polish table, chrzan is especially prominent during Wielkanoc (Easter), when it is placed in the święconka (blessed basket) alongside other symbolic foods and later served with jajka (eggs), wędliny (cold cuts), and żurek (sour rye soup).

The powerful aroma and taste of chrzan are believed to represent strength, health, and renewal, which is why it has been a part of Polish seasonal feasting for centuries. Prepared by finely grating the root of the chrzan pospolity (common horseradish plant), often mixed with ocet (vinegar), śmietana (sour cream), or buraki (beets), it takes on several forms, from a pure white paste to a vivid pink mixture called ćwikła z chrzanem (beetroot with horseradish), a staple during holiday meals. The preparation of chrzan is not for the faint of heart—its pungency can bring tears to the eyes, which is part of its charm and folklore.

In older Polish kitchens, grating fresh korzeń chrzanu (horseradish root) was almost a ceremonial act, often entrusted to the strongest or most tear-resistant member of the household. Beyond the kitchen, chrzan has found its place in folk medicine as well, with infusions and poultices used to treat colds, joint pain, and respiratory issues, demonstrating its role as both food and remedy. In rural Poland, it was common to plant chrzan near the house or barn not only for culinary purposes but also to protect against złe moce (evil forces)—a belief rooted in Slavic paganism that lingered into Christian traditions.

Regional variations of chrzanowe przetwory (horseradish preserves) can be found throughout Poland, particularly in Małopolska, Podlasie, and Śląsk, where local recipes include secret combinations of herbs, root vegetables, or even a touch of miód (honey). Today, jars of tarty chrzan (grated horseradish) are ubiquitous in Polish supermarkets, but many still prefer homemade versions passed down through family lines.

Whether served alongside karkówka (pork neck), białą kiełbasą (white sausage), or used to season galareta (meat in aspic), chrzan elevates simple ingredients with its fiery edge.

CZEKOLADA WEDEL

CZEKOLADA WEDEL (Wedel chocolate) is not merely a confection—it is a deeply embedded part of Polish cultural memory, national pride, and the evolution of urban taste. Founded in 1851 by Karol Wedel, a German-born entrepreneur who made Warsaw his home, the company quickly became synonymous with luxury, innovation, and Polish sweetness. The iconic brand, often referred to simply as Wedel, introduced Poland to czekolada mleczna (milk chocolate) and crafted some of the most beloved treats in the country, such as Ptasie Mleczko (Bird’s Milk), a delicate marshmallow-like candy coated in chocolate, and torcik Wedlowski (Wedel torte), an intricately decorated chocolate wafer cake.

In pre-war Warszawa (Warsaw), a visit to the original Pijalnia Czekolady Wedla (Wedel Chocolate Lounge) on ulica Szpitalna was a mark of refined taste and modern sophistication. The café, with its marbled interiors and polished counters, served rich gorąca czekolada (hot chocolate), layered cakes, and handmade truffles to artists, aristocrats, and everyday Warsaw citizens who wanted a taste of the good life. During the PRL (People’s Republic of Poland) period, Wedel was nationalized, but remarkably, the company retained much of its original character and reputation for quality. Despite economic hardship, czekolada Wedel remained a coveted gift, a reward for children, and a special treat during święta (holidays). Even today, older generations recall the thrill of receiving a bar of czekolada nadziewana (filled chocolate) or a box of bombonierki Wedla (Wedel chocolates) with nostalgia and affection. In the post-communist era, Wedel returned to private ownership and has since reestablished itself as a premium brand, exporting to dozens of countries while continuing to produce beloved classics.

The packaging, often featuring the founder’s handwritten signature and elegant vintage artwork, evokes a sense of continuity and legacy. Modern Wedel also collaborates with Polish artists and chefs, creating limited edition collections and experimental flavors that keep the brand dynamic. Beyond its products, Wedel symbolizes Poland’s ability to blend tradycja (tradition) with nowoczesność (modernity), maintaining quality and charm across turbulent historical shifts. Whether shared on a train ride, given on Walentynki (Valentine’s Day), or enjoyed during a stroll through Warsaw, czekolada Wedel is a taste of Poland’s cultural journey—sweet, rich, sometimes bittersweet, but always unmistakably Polish.

DZIEDZINIEC

DZIEDZINIEC (courtyard) is a quintessential element of Polish architecture, found at the heart of both kamienice (townhouses) in urban centers and dwory (manor houses) in the countryside, acting as a physical and symbolic space of connection, transition, and life. The traditional dziedziniec serves not only as a practical space—used for entry, circulation, or even agriculture—but also as an emotional and social core where neighbors meet, children play, and stories unfold. In cities like Kraków, Lublin, or Łódź, walking through a brama (gateway) into a dziedziniec reveals an intimate world hidden behind façades, where laundry lines stretch above cobblestones, klatki schodowe (stairwells) echo with voices, and tiny gardens flourish against the odds. These courtyards, often enclosed by multi-story tenement buildings, carry the patina of decades—tynki (plasters) cracked with time, kratki (grilles) rusting with charm, and ivy creeping up old walls.

During the PRL era, the dziedziniec sometimes became a shared economic space—used for storage, small-scale commerce, or communal gatherings—offering residents a rare form of semi-private, semi-public autonomy amid cramped apartments and limited amenities. In rural Poland, the dziedziniec of a dworek (manor house) or zagroda (homestead) was typically more open, ringed by stodoły (barns), obora (cowsheds), and the dom mieszkalny (residential house), organized around a functional and symbolic center. Here, the dziedziniec reflected hierarchy, with social life flowing outward from the main house to the edges of labor. In both rural and urban settings, the dziedziniec often doubled as the stage for rituals and customs—kolędowanie (caroling), wesela (weddings), and stypy (wakes)—anchoring community through continuity. Today, there is a growing movement to revitalize Poland’s historic dziedzińce, especially in neglected post-industrial cities where these spaces have suffered decay.

Architects and preservationists are working to restore dziedzińce not only for their aesthetic value but for their role in rebuilding sąsiedzkość (neighborliness) and tożsamość lokalna (local identity). Many newly restored dziedzińce now feature art installations, cafes, or open-air galleries that blend old brickwork with contemporary interventions, inviting residents and visitors alike to experience Poland’s architectural heart from within.

FLISACY

FLISACY (rafters) are the often-overlooked heroes of Poland’s riverine heritage, guardians of an ancient trade that once linked the highlands to the Baltic Sea and shaped the economic and cultural fabric of the country. Known for navigating large wooden tratwy (rafts) down rivers like the Dunajec, Wisła, and San, the flisacy were more than transporters—they were craftsmen, navigators, and cultural carriers whose seasonal journeys stitched together distant regions of Poland. These men, clad in traditional kapelusze flisackie (rafter hats) and heavy woolen kamizelki (vests), commanded rafts made from freshly felled pnie drzew (tree trunks), lashed together with natural fibers and controlled by long drągi (poles) that guided them through rocky rapids, swirling currents, and narrow gorges. The life of a flisak (rafter) was arduous and risky, but it also carried a distinct pride and camaraderie, enriched by centuries of ritual, songs, and storytelling.

One of the most picturesque remnants of this tradition is still practiced in Pieniny, where modern flisacy ferry tourists along the dramatic Przełom Dunajca (Dunajec Gorge), donning the traditional strój flisacki (rafter costume) and sharing tales of local legends and river spirits like baba z wody (water hag) or krasnoludki rzeczne (river dwarves). Historically, the flisacy played a crucial role in the timber and salt trade, transporting sól bocheńska (Bochnia salt) and drewno (wood) from southern forests to ports in Gdańsk, where the goods would be sold and exported. Along the way, they would stop in karczmy (inns) and przystanie (river ports), forming their own subculture with distinctive dialects, songs called flisackie pieśni, and even their own patron saint—święty Nepomucen, protector of those who work on water. In literature and Polish folklore, flisacy appear as noble, romantic figures, free spirits of the river who braved nature and fate with equal courage.

Though the commercial rafting trade declined in the 19th and 20th centuries due to the rise of railways and roads, the legacy of the flisacy endures in festivals, reenactments, and the continued use of river traditions in regional identity, especially in Małopolska and Podkarpacie.

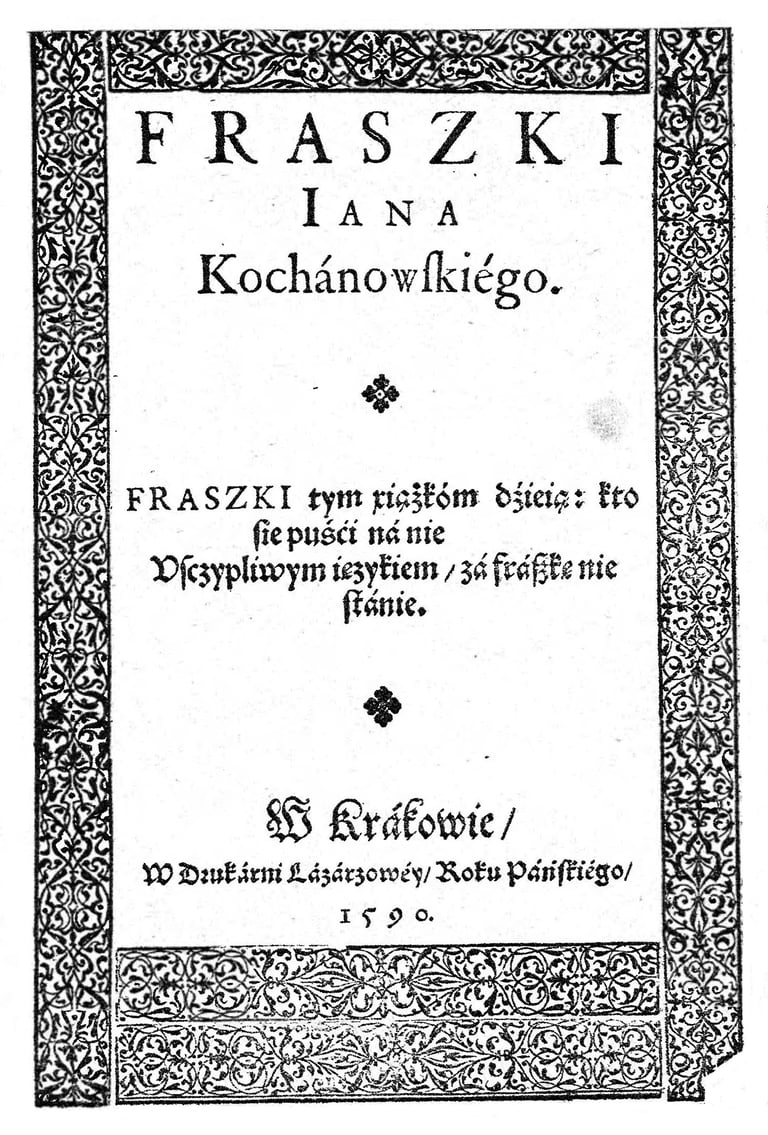

FRASZKA

FRASZKA (epigram) is a uniquely Polish literary form that captures the national wit, wisdom, and worldview in miniature. Typically brief, playful, and pointed, a fraszka is a poetic gem—concise in length but expansive in meaning—often ending with a twist or unexpected insight. The form was elevated to literary prominence by Jan Kochanowski, one of Poland’s greatest Renaissance poets, whose collection "Fraszki" published in the late 16th century remains a cornerstone of Polish literature. In these works, Kochanowski masterfully observed the everyday—uczta (feast), miłość (love), śmierć (death), przyjaźń (friendship)—and infused each with moral reflection, humor, or satirical sting. His famous lines like “Na zdrowie” (On health) and “O żywocie ludzkim” (On human life) reveal not only philosophical depth but an enduring Polish preoccupation with the fragility and irony of existence.

The term fraszka itself is derived from the Italian “frasca,” meaning trivial or witty remark, yet in the Polish context, these so-called trifles often carry surprising weight. They dwell on topics such as przemijanie (passing of time), pijaństwo (drunkenness), duma (pride), or głupota ludzka (human folly), making them both timely and timeless. Throughout the centuries, fraszki became a favorite genre among szlachta (nobility) and inteligencja (intelligentsia), recited in salons, scribbled in letters, or shared at uczty szlacheckie (noble feasts) where wordplay and poetic skill were signs of education and social grace. The structure is often based on rym parzysty (couplet rhyme) or simple czterowiersz (quatrains), though the true art lies in rhythm, brevity, and punch. In modern times, the fraszka continues to inspire poets, journalists, and political commentators, often used in felietony (opinion columns) or public speeches to add color, critique, or charm.

High school students study fraszki not only as literary forms but as cultural mirrors, revealing Polish humor, irony, and stoicism in the face of adversity. The adaptability of the fraszka allows it to survive in memes, satirical tweets, and social media captions, proving that this poetic form—though centuries old—still resonates in contemporary expression. Whether playful or profound, a fraszka demands wit, economy, and elegance, reflecting a national talent for saying much with little. Like Poland itself, the fraszka dances between levity and depth, laughter and lament, offering a sliver of truth wrapped in clever rhyme—a poetic snapshot of the Polish spirit.

GOLONKA

GOLONKA (pork knuckle) is a rich and flavorful cornerstone of Polish culinary tradition, celebrated not only for its indulgent taste but for its role in feasting culture, tavern lore, and rustic hospitality. Often slow-braised or roasted to perfection, golonka is the epitome of kuchnia staropolska (Old Polish cuisine), where bold, hearty ingredients take center stage and meals are events rather than mere sustenance. The dish consists of a hefty staw skokowy wieprzowy (pig’s hind shank), typically marinated in czosnek (garlic), majeranek (marjoram), piwo (beer), and other spices, then cooked until the skórka (skin) becomes golden and crisp while the mięso (meat) falls tenderly from the bone. This succulent dish is a staple in traditional karczmy (Polish taverns), where it’s often served with kapusta zasmażana (fried cabbage), ziemniaki (potatoes), or chrzan (horseradish) to cut through the richness.

In many households, golonka is a centerpiece of special gatherings such as urodziny (birthdays), imieniny (name days), or święta (holidays), where the ritual of carving and sharing the meat reinforces community and gościnność (hospitality). Though once considered a peasant dish due to its use of less refined cuts, golonka has ascended to cult status among food lovers who seek out authentic, slow-cooked flavors that speak of history and place. In regions like Śląsk (Silesia) and Małopolska, you’ll find regional variations—some smoked, others roasted over open fire, and still others slow-stewed in clay ovens, infused with local beer and served with thick slices of chleb wiejski (country bread). For many Poles, the sight of a massive, glistening golonka on a wooden board signals celebration, indulgence, and sytość (fullness). It pairs naturally with a mug of piwo rzemieślnicze (craft beer) or a shot of wódka żytnia (rye vodka), emphasizing its role not just as food but as a sensory event.

In contemporary gastronomy, golonka has seen reinvention—appearing in gourmet form in upscale restaurants, sometimes accompanied by puree z selera (celeriac purée) or musztarda miodowa (honey mustard), showing the versatility and continued relevance of this once-humble dish. Yet at its core, golonka remains a proud emblem of tradycja kulinarna (culinary tradition), where flavor, history, and identity simmer together. Whether devoured in a village inn or savored in a city bistro, it tells a story of Polish appetite—robust, generous, and rooted in the earthy abundance of the land.

HUSARIA

HUSARIA (winged hussars) are perhaps the most iconic military formation in Polish history, immortalized not only for their battlefield prowess but for their striking appearance, cultural symbolism, and lasting impact on national identity. Emerging in the 16th century and reaching their zenith in the 17th, the husaria were elite kawaleria ciężka (heavy cavalry) known for their fearlessness, discipline, and spectacular charges that could shatter enemy lines with devastating force. What distinguished them most, visually and psychologically, were the towering skrzydła (wings) affixed to their backs or saddles—constructed from wooden frames adorned with eagle, goose, or swan feathers. These skrzydła husarskie (hussar wings) were not just decorative; they served to intimidate enemies, muffle the sound of galloping horses, and possibly deflect lasso tatarskie (Tatar lassos) used in combat. Clad in zbroja płytowa (plate armor), wielding long kopie (lances), szable (sabres), and pistolety skałkowe (flintlock pistols), the husarze were not only warriors but symbols of polska potęga (Polish might) and the chivalric ethos of the Rzeczpospolita Obojga Narodów (Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth).

They played a decisive role in battles such as Kircholm (1605), Kłuszyn (1610), and most famously Wiedeń (1683)—the Battle of Vienna—where under the command of król Jan III Sobieski (King John III Sobieski), they led a charge that broke the Ottoman siege and altered the course of European history. Their tactics emphasized speed, formation, and psychological warfare, often turning the tide of battles even when outnumbered. Culturally, the husaria came to embody the spirit of the sarmacki etos (Sarmatian ethos), which idealized the Polish noble as both cultured and fiercely independent. This vision lives on in art, literature, and national myth, where the husarze are portrayed as guardians of faith, freedom, and homeland. During the partitions, when Poland was erased from the map, images of husaria adorned paintings, poems, and even revolutionary banners as symbols of a lost glory and the hope of resurgence.

Today, reenactment groups proudly don zbroje husarskie (hussar armor) at national festivals, military parades, and educational events, keeping the memory alive. Museums across Poland—especially in Kraków, Warszawa, and Malbork—display authentic hełmy, pancerze, and skrzydła, allowing visitors to stand in awe of these relics of martial artistry. In the Polish imagination, husaria remains more than history; it is a metaphor for resilience, bravery, and the sublime blend of aesthetics and force. They charge still—not across battlefields, but through the national psyche, a winged reminder of the strength and grandeur Poland once wielded and still carries within.

JASNA GÓRA

JASNA GÓRA (Bright Hill) in Częstochowa stands as the spiritual heart of Poland, a place of profound religious, national, and emotional resonance that transcends its role as a monastery. Dominated by the revered icon of the Matka Boska Częstochowska (Our Lady of Częstochowa), also known as the Czarna Madonna (Black Madonna), Jasna Góra is not merely a sanctuary—it is a symbol of Polish endurance, identity, and faith across centuries of upheaval. Pilgrims from all corners of the country and beyond walk or travel to this sacred site in acts of pielgrzymka (pilgrimage), often barefoot, carrying krzyże (crosses), różańce (rosaries), and prayers on behalf of families, communities, and the nation itself. The monastery, founded in the 14th century by the paulini (Pauline Fathers), gained national prominence in 1655 during the Potop szwedzki (Swedish Deluge), when the small monastic garrison miraculously withstood a siege by invading forces. This defense was hailed as divine intervention, and the Czarna Madonna was officially declared Królowa Polski (Queen of Poland) by King Jan Kazimierz in 1656—a title that still resonates deeply with Polish Catholics.

The icon itself, darkened over centuries by candle smoke and legend, is believed by many to be miraculous, credited with healings, victories, and personal transformations. Encased in gold and adorned with wota (votive offerings) of kings, generals, and humble citizens, the image draws over four million pilgrims annually. They gather in the Kaplica Cudownego Obrazu (Chapel of the Miraculous Icon), where daily msze święte (holy masses) and apel jasnogórski (Jasna Góra appeal) are held, culminating in silent, communal reverence when the image is unveiled with solemn ceremony. The monastery complex itself is architecturally rich, with baroque bazylika, skarbce (treasuries), and muzeum (museum) housing centuries of Polish sacred art, battle banners, and royal gifts.

Throughout modern history, Jasna Góra has remained a beacon of moral authority and spiritual resistance. During the communist era, it served as a bastion of wiara (faith) and tożsamość narodowa (national identity), hosting gatherings that subtly defied state atheism. Pope Jan Paweł II (John Paul II) visited multiple times, calling it the "altar of the nation" and reinforcing its place in Polish Catholicism. Today, it continues to inspire not only the devout but also those seeking cultural roots, emotional solace, or a connection to the collective memory of a people shaped by suffering, courage, and hope. Jasna Góra is more than a hill—it is a summit of Polish soul, where belief and history ascend together.

KATARYNIARZ

KATARYNIARZ (organ grinder) is a vanishing figure from Poland’s urban folklore, once a familiar and beloved presence in the streets of Warszawa, Lwów, Kraków, and other bustling cities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The kataryniarz, often accompanied by a small małpka (monkey) or piesek tresowany (trained dog), turned the crank of a wooden katarynka (barrel organ) to produce mechanically-driven music—waltzes, mazurkas, polkas, and sentimental songs that echoed between tenements and marketplaces. Dressed in a slightly worn yet theatrical outfit, with a bowler hat or kaszkiet (cap), the kataryniarz brought not just melody but atmosphere to working-class neighborhoods and courtyards, where children danced and adults tossed monety (coins) into his tin cup or open case. For many city dwellers, he was a bearer of cheer, of nostalgia, and sometimes even melancholy, his tunes a soundtrack to the bittersweet rhythm of urban life.

Despite his modest appearance, the kataryniarz held an important social role—as a messenger of popular culture, a mobile jukebox before the age of radio, and a performer whose music often carried słowa uliczne (street lyrics) full of satire, longing, or local gossip. Some were war veterans, others blind or disabled, who used the craft to support themselves with dignity. However, the katarynka was not always universally welcomed. In bourgeois society, especially in late partition-era Warszawa, the grinding of the organ was seen by some as disruptive, even vulgar, leading to frequent zakazy katarynek (organ bans) and public debates about the aesthetic of city life. These tensions are famously captured in Bolesław Prus’s short story Katarynka, in which a grumpy bourgeois man is gradually softened by the effect of an organ grinder’s tune on a blind girl.

Technologically, the katarynka was a marvel of craftsmanship, using pinned cylinders or perforated cards to mechanically play popular melodies, often imported from Niemcy (Germany) or adapted from pieśni ludowe (folk songs). Some larger models even featured moving puppets or figury religijne (religious figures), adding theatricality to the performance. Today, the figure of the kataryniarz survives largely in memory, literature, and occasional reenactments at heritage festivals, especially in districts like Praga in Warsaw, where nostalgia for the czasy przedwojenne (pre-war times) runs deep. Restored katarynki are now treasured by collectors and museums, and their whimsical, wheezing songs remain etched in the collective imagination. The kataryniarz may have vanished from Poland’s sidewalks, but he continues to turn his crank in the national heart—a reminder of joy found in simple art, and of a time when music wandered freely, echoing through the cobbled streets of a changing world.

KOŁACZ

KOŁACZ (ceremonial bread) is a deeply symbolic and festive element of Polish tradition, baked not only for nourishment but for celebration, blessing, and honor. This round, often elaborately decorated bread appears at major life events—wesela (weddings), chrzty (baptisms), dożynki (harvest festivals), and święta religijne (religious holidays)—carrying meanings of gościnność (hospitality), uroczystość (ceremony), and dostatek (abundance). The word kołacz comes from the Slavic root for “circle,” referencing both its shape and its spiritual connotation: a symbol of eternity, unity, and continuity. Traditionally prepared from enriched dough—made with jaja (eggs), masło (butter), and mąka pszenna (wheat flour)—the kołacz may be filled with ser biały (white cheese), mak (poppy seed), or powidła śliwkowe (plum jam), and topped with braided designs, kruszonka (crumble), or lukier (icing).

At Polish weddings, the kołacz weselny (wedding bread) is presented by the bride and groom’s parents as a blessing, accompanied by sól i wódka (salt and vodka) in a ritual that represents the dual nature of life—bittersweet and joyful. The couple breaks and eats the bread, a gesture of unity and commitment, often followed by cheers of na zdrowie (to your health) from the gathered guests. In rural areas, especially in Małopolska, Podkarpacie, and Lubelszczyzna, the kołacz is also baked for dożynki, where it’s carried in a procession by dziewczęta w strojach ludowych (girls in folk costumes) and offered to the village head or priest in gratitude for the harvest. Its presence at the table or altar is a gesture of sacred and communal gratitude, connecting labor, land, and divinity.

In modern Polish homes, the kołacz is sometimes prepared for Boże Narodzenie (Christmas) or Wielkanoc (Easter), sharing the table with other symbolic foods like babka, mazurek, and chleb święcony (blessed bread). Recipes vary by region and family tradition, with some versions incorporating rodzynki (raisins), migdały (almonds), or even skórka pomarańczowa (orange peel). The act of baking a kołacz is often a communal one—grandmothers, mothers, and daughters working side by side, shaping the dough with intention, often invoking błogosławieństwo (blessing) through gesture and song. Though commercial versions can now be found in bakeries, the handmade kołacz retains a powerful aura, standing as more than a dessert—it is a ritual object, a gift, a prayer in edible form.

The kołacz links the sacred and the everyday, its circular form echoing the rhythms of Polish life—birth, marriage, harvest, and remembrance. Whether placed on an embroidered serweta (tablecloth) or passed hand to hand in a bustling village yard, it carries the warmth of the oven and the soul of the occasion, nourishing both body and tradition in one timeless offering.

KOMPANIA HONOROWA

KOMPANIA HONOROWA (honor guard) is one of the most solemn and visually striking elements of Poland’s military tradition, embodying the values of godność (dignity), szacunek (respect), and państwowość (statehood). Composed of elite soldiers selected for their discipline, stature, and ceremonial excellence, the kompania honorowa represents the Polish Armed Forces during state events, military funerals, national holidays, and visits by foreign dignitaries. Their presence signals not only protocol but national reverence, connecting contemporary Poland with centuries of martial tradition and symbolic ritual. Clad in meticulously pressed mundury galowe (dress uniforms)—often featuring ornate czapki rogatywki (four-pointed caps), polished pasy skórzane (leather belts), and gleaming buty oficerskie (officer boots)—they move with near-mechanical precision, executing musztra paradna (ceremonial drill) in perfect unison.

The most visible moments of the kompania honorowa occur during uroczystości państwowe (state ceremonies), such as Święto Wojska Polskiego (Armed Forces Day), Święto Konstytucji 3 Maja (Constitution Day), or during the changing of the guard at the Grób Nieznanego Żołnierza (Tomb of the Unknown Soldier) in Warszawa (Warsaw). There, the guard stands in stoic silence beneath the open sky, honoring all fallen soldiers whose names remain unknown but whose sacrifice is eternal. The ritual of zmiana warty (changing of the guard) draws locals and tourists alike, mesmerized by the flawless timing, synchronized steps, and commanding presence of the żołnierze kompanii honorowej (honor guard soldiers).

Each branch of the military—wojska lądowe (land forces), marynarka wojenna (navy), and siły powietrzne (air force)—has its own ceremonial unit, trained not only in protocol but in the historical and symbolic significance of their role. Their weapons, usually ceremonial karabiny SKS (SKS rifles), are carried with precise angles and rhythms, part of an intricate dance of tradition and reverence. For many Poles, the kompania honorowa evokes deep emotion, particularly when it participates in pogrzeby państwowe (state funerals), laying to rest national heroes, resistance fighters, or esteemed cultural figures with full military honors—salwa honorowa (honor salvo), trębacz (bugler), and the folding of the biało-czerwona flaga (white-and-red flag).

KURONIÓWKA

KURONIÓWKA (Kuroń’s benefit) is a term that emerged in the 1990s in Poland to describe a specific form of zasiłek dla bezrobotnych (unemployment benefit), named after Jacek Kuroń, a legendary social activist, dissident, and later Minister of Labor and Social Policy. During the early years of Poland’s transformacja ustrojowa (political and economic transformation) from communism to capitalism, the abrupt collapse of state industries led to mass layoffs and widespread joblessness. In response, Kuroń introduced a generous state-supported zasiłek socjalny (social allowance) to provide immediate relief to newly unemployed workers, especially those from sectors hit hardest by privatization and restructuring. While officially a serious and essential social policy tool, it quickly became known colloquially as kuroniówka, capturing both its origin and its popular perception as a lifeline during a turbulent time.

The kuroniówka was designed to ensure minimum egzystencji (minimum subsistence) and was easy to access, particularly in the early 1990s when entire towns—especially in Górny Śląsk (Upper Silesia) and Łódź—were affected by the closing of textile plants, mines, and heavy industries. For many, it was the only means of surviving the brutal shock of the market economy. However, over time, kuroniówka took on a controversial tone. Critics argued that it created a pułapka bezczynności (trap of inactivity) and discouraged job-seeking, especially as some recipients remained unemployed for extended periods while receiving consistent benefits. Yet for others, the kuroniówka became a symbol of solidarność społeczna (social solidarity) in a moment when the state was rapidly retracting from many areas of public life.

Jacek Kuroń himself, known for his lifelong fight for sprawiedliwość społeczna (social justice) and his role in the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement, remained unapologetic, emphasizing that no transition could be moral without protecting the vulnerable. The benefit he championed helped calm social unrest and gave dignity to people who had spent their entire adult lives working in state-owned enterprises, only to find themselves suddenly bez pracy (jobless), bez perspektyw (without prospects), and bez oszczędności (without savings). In time, reforms tightened the eligibility and reduced the payouts, aligning the policy with more standard European welfare models, but the term kuroniówka remains embedded in Polish memory.

To this day, kuroniówka functions as both a historical artifact and a shorthand in public discourse—used to reference debates about państwo opiekuńcze (welfare state), wykluczenie społeczne (social exclusion), and the moral obligations of capitalism. It reminds Poland of a time when economic liberation came with immense human cost and how one man’s vision of fairness helped cushion the blow.

LAJKONIK

LAJKONIK (the Lajkonik) is one of the most whimsical and beloved figures in Polish folklore, celebrated annually in Kraków during a vibrant and surreal procession that blends legend, humor, and centuries-old tradition. Dressed in ornate stroje tatarskie (Tatar costume) complete with a pointed czapka (hat), flowing kaftan (robe), and perched atop a wooden koń na kiju (hobby horse), the Lajkonik parades through the streets of Stare Miasto (Old Town) every June, accompanied by musicians, dancers, and crowds of cheering locals. The origin of the Lajkonik tradition is rooted in medieval legend: during a Tatar invasion in the 13th century, local raftsmen, or flisacy, from the Zwierzyniec district supposedly defeated the invaders and returned in triumph wearing their garb. To commemorate this victory, the ritual was born—a humorous inversion of terror into celebration, fear into festivity.

The modern pochód lajkonika (Lajkonik parade) starts at the klasztor Norbertanek (Norbertine Monastery) and winds its way to the Rynek Główny (Main Market Square), where the Lajkonik performs a ceremonial dance before the mayor of Kraków, who symbolically offers a haracz (tribute) to ensure the city’s safety. Along the way, the Lajkonik taps bystanders with his buława (mace), a gesture believed to bring szczęście (good luck) and pomyślność (prosperity) for the year to come. Children laugh, music from traditional kapela lajkonikowa (Lajkonik band) fills the air, and people in elaborate costumes re-enact elements of the legend, creating an atmosphere that feels timeless yet utterly alive.

Though humorous in tone, the tradition of the Lajkonik is layered with symbolism. It represents przemiana lęku w radość (the transformation of fear into joy), a celebration of communal victory, and a living memory of Kraków’s endurance through centuries of invasion and resilience. In the communist era, the Lajkonik continued to appear—sometimes sanitized, sometimes subversively—reminding citizens of Kraków’s distinct identity in the face of imposed uniformity. Today, the pochód is one of the city’s most cherished events, recognized by UNESCO as part of Poland’s niematerialne dziedzictwo kulturowe (intangible cultural heritage).

Beyond the annual procession, the figure of the Lajkonik has become a symbol of Kraków itself, featured on logos, souvenirs, performances, and school curricula. Tourists pose with statues of him; locals pass down the legend; and artists reinterpret his form in paintings, music, and literature. The Lajkonik endures not merely as a folkloric character, but as a jester-warrior of Polish memory—riding through centuries with a wink and a flourish, uniting Kraków in a dance of laughter, defiance, and unbroken tradition.

MAKOWIEC

MAKOWIEC (poppy seed roll) is one of the most iconic and cherished desserts in Polish culinary tradition, inseparable from święta (holidays), rodzinne uroczystości (family celebrations), and the comforting rhythm of seasonal baking. A beautiful spiral of sweet, yeasty dough filled with rich masa makowa (poppy seed filling), makowiec graces tables across Poland during Boże Narodzenie (Christmas), Wielkanoc (Easter), and imieniny (name days), symbolizing urodzaj (abundance), płodność (fertility), and pomyślność (good fortune). The use of mak (poppy seed) in Polish desserts dates back centuries and carries layers of meaning, from pre-Christian Slavic rites to Catholic symbolism, where poppy seeds were believed to bring blessings and protect the home from złe duchy (evil spirits).

To prepare a traditional makowiec, bakers soak and grind the poppy seeds, then combine them with miód (honey), bakalie (dried fruits and nuts), skórka pomarańczowa (candied orange peel), and sometimes a touch of rum or wanilia (vanilla). This aromatic mixture is then spread generously over a sheet of ciasto drożdżowe (yeast dough), carefully rolled into a log, and baked until golden. The result is a moist, tender loaf with a hypnotic swirl of black and gold, often topped with lukier (icing) or kruszonka (streusel). Each slice reveals not just taste but kunszt domowy (domestic artistry), the loving labor of generations who have passed down their recipes and techniques.

In some regions, such as Małopolska or Podlasie, makowiec takes slightly different forms—wrapped in parchment for a tighter roll, layered like a strudel, or even made into makowiec japoński, a version with added jabłka (apples) for extra moisture. During wigilia (Christmas Eve dinner), makowiec is one of the traditional twelve dishes, each symbolizing a month or a wish for the new year. It’s not uncommon to find the table adorned with makówki (poppy seed pudding) or kutia, but makowiec remains the most visually spectacular and universally beloved.

Beyond its role as a dessert, makowiec is a carrier of memory. The scent of baking poppy seeds evokes childhood kitchens, the hum of family conversation, and the quiet ritual of slicing the roll with care, ensuring that the spirala maku (poppy spiral) remains unbroken. In contemporary Poland, makowiec can be found in both home kitchens and cukiernie (pastry shops), where modern bakers may experiment with gluten-free or vegan versions, but the essence remains unchanged: a roll of sweetness, patience, and warmth. With every bite, makowiec offers a taste of Polish heritage—layered, generous, and made to be shared.

MALBORK

MALBORK (Malbork Castle) is one of the grandest and most awe-inspiring medieval fortresses in all of Europe, a monumental testament to Poland’s Gothic architectural heritage and complex history. Built in the 13th century by the zakon krzyżacki (Teutonic Order), this sprawling zamek ceglany (brick castle) sits majestically on the banks of the rzeka Nogat (Nogat River) in northern Poland, its red towers, high walls, and intricate courtyards reflecting the ambition and might of its original builders. Known in German as Marienburg, it served as the capital of the Teutonic Knights—a religious and military order of German crusaders—until it was eventually incorporated into the Kingdom of Poland during the reign of Kazimierz Jagiellończyk (Casimir IV Jagiellon) in 1457, following the decline of the Order after the wojna trzynastoletnia (Thirteen Years' War).

Spanning over 20 hectares, Malbork is the largest brick castle in the world by surface area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, celebrated for its staggering scale, meticulous restoration, and cultural significance. The castle is divided into three parts: Zamek Wysoki (High Castle), Zamek Średni (Middle Castle), and Zamek Niski (Low Castle), each featuring a labyrinth of dziedzińce (courtyards), kaplice (chapels), refektarze (refectories), and defensive towers. Within its red-brick walls lies a rich collection of medieval artifacts, including zbroje rycerskie (knightly armor), miecze (swords), chorągwie (banners), and intricate witraże (stained glass). The komnaty mistrza zakonu (Grand Master's chambers) reveal the austere grandeur in which the order’s leadership once lived and ruled, while the castle’s skarbiec (treasury) and muzeum bursztynu (amber museum) showcase Poland’s connection to trade and artistry.

Malbork also serves as a powerful narrative site, embodying Poland’s long struggle for sovereignty, resilience, and identity. Severely damaged during II wojna światowa (World War II), the castle underwent decades of painstaking restoration, symbolizing Poland’s commitment to preserving its dziedzictwo kulturowe (cultural heritage). Today, it is a major tourist destination, hosting nocne zwiedzanie (night tours), turnieje rycerskie (knightly tournaments), and rekonstrukcje historyczne (historical reenactments) that bring its epic past to life. The annual Oblężenie Malborka (Siege of Malbork) festival attracts thousands of visitors, who come to witness staged battles, medieval music, and crafts demonstrations within the castle’s formidable walls.

Beyond its bricks and battlements, Malbork stands as a symbol of layered identity—a place where krucjaty (crusades), królowie (kings), and obywatele (citizens) converge across centuries. It invites visitors not only to marvel at architectural prowess but to reflect on the enduring forces of conflict, faith, and reconciliation that shaped Poland’s story. To walk its corridors is to touch history—to feel the echo of footsteps, the weight of time, and the majesty of a fortress that still guards the soul of a nation.

MAZURKA

MAZURKA (mazurka) is one of Poland’s most distinctive contributions to world music and dance—a lively, rhythmically complex folk dance that evolved into a refined artistic form through centuries of tradition, passion, and reinvention. Rooted in the Mazowsze (Mazovia) region, the mazurka is characterized by its metrum trójdzielne (triple meter), strong accent on the druga lub trzecia nuta (second or third beat), and an ever-changing interplay of tempo, gesture, and improvisation. Originally danced in village gatherings called wiejskie zabawy, the mazurka was performed in pairs or small groups, often accompanied by a band playing skrzypce (violins), basy (folk bass), and klarnety (clarinets), creating a rustic but highly energetic atmosphere filled with stomping feet, swirling skirts, and spontaneous calls from the dancers.

There are several regional types of mazurka, including the kujawiak (slower, more melancholic), oberek (faster, more acrobatic), and mazur właściwy (proper mazurka), each with distinct steps and moods, yet all sharing the common thread of polski charakter taneczny (Polish dance character). In the 18th and 19th centuries, the mazurka rose from village barns to royal courts and salony szlacheckie (noble salons), where it was embraced by the szlachta (Polish nobility) as a symbol of national culture. Danced with ceremonial elegance and military flair, it became a fixture of formal balls and patriotic events, where each ukłon (bow), obrót (spin), and przytup (stomp) conveyed not just movement, but social code and identity.

The transformation of the mazurka into a musical form was immortalized by Fryderyk Chopin, who composed over 50 mazurki fortepianowe (mazurkas for piano), infusing folk rhythm with emotional depth and harmonic richness. For Chopin, the mazurka was more than dance—it was muzyczna ojczyzna (a musical homeland), through which he could express nostalgia, longing, and pride in Polishness even in exile. His compositions brought the mazurka to European concert halls, where its lilting rhythms and ornamental phrases captivated audiences and inspired generations of composers from Karol Szymanowski to Igor Stravinsky.

Today, the mazurka lives on in multiple forms—revived in zespoły ludowe (folk ensembles), taught in domy kultury (community cultural centers), and reimagined by classical pianists and jazz musicians alike. It remains a staple of tańce narodowe polskie (Polish national dances), performed at festivals, weddings, and cultural showcases, both at home and among the Polish diaspora. Whether pounded out on village floors or interpreted on concert pianos, the mazurka continues to dance across time and space, a resilient thread in the rich tapestry of Polish rhythm, identity, and soul.

MORS

MORS (ice swimmer) is a unique and spirited figure in Polish winter culture, known for plunging into icy waters with a combination of cheerfulness, resilience, and a deep belief in the invigorating power of cold. The word mors—from the Polish for “walrus”—has become synonymous with members of the country’s vibrant kluby morsów (ice swimming clubs), who gather from late autumn through early spring to bathe in freezing lakes, rivers, and the Morze Bałtyckie (Baltic Sea), often surrounded by snow and curious onlookers. What may seem extreme to outsiders is, for many Poles, a joyful ritual and a path to hart ducha (mental fortitude), odporność (immunity), and dobry nastrój (good mood).

The practice of morsowanie (ice swimming) gained popularity in Poland in the late 20th century and has grown rapidly in recent years, attracting people of all ages who embrace the experience not only as a health regimen but as a social event. Weekly winter dips are typically preceded by a rozgrzewka (warm-up session) involving ćwiczenia fizyczne (physical exercises) like jumping jacks or jogging in place, followed by a communal plunge—sometimes lasting mere seconds, sometimes several minutes. Participants often wear only swimsuits, czapki wełniane (wool hats), and rękawiczki (gloves), with bright red faces and laughter echoing across the icy water.

Though there’s no single profile of a mors, many describe the activity as addictive, with reported benefits ranging from increased energy and reduced inflammation to a heightened sense of samopoczucie (well-being). Some clubs even promote morsowanie z sauną (ice swimming combined with sauna sessions), creating a Scandinavian-like ritual in Polish mountain resorts and lake districts. In cities like Gdynia, Szczecin, and Olsztyn, thousands gather each year for organized events, such as the Światowy Dzień Morsa (World Walrus Day), complete with costumes, live music, and friendly competitions. Many swimmers dress in przebrania karnawałowe (carnival costumes), turning the frozen plunge into a celebration of absurdity, courage, and communal warmth.

In Polish culture, the mors has become more than a seasonal oddity—he or she is a symbol of vitality, endurance, and the ability to find joy in discomfort. As Poland faces long, dark winters, morsowanie serves as a defiant embrace of the cold, an assertion that ruch to zdrowie (movement is health) and that even the harshest conditions can be transformed into rituals of life, laughter, and connection. Whether surrounded by ice floes or slushy mud, the mors dives in not to escape winter, but to meet it with open arms and a wide grin.

OGÓREK KISZONY

OGÓREK KISZONY (pickled cucumber) is far more than just a food item in Poland—it is a staple of the national palate, a symbol of culinary heritage, and a flavorful thread woven through countless meals, gatherings, and traditions. The ogórek kiszony, known for its tangy, briny bite and satisfying crunch, is made through kiszenie (fermentation), an ancient method of preservation that transforms fresh cucumbers into probiotic-rich delicacies. Unlike vinegared pickles, the Polish version relies on natural fermentacja mlekowa (lactic acid fermentation), where cucumbers are submerged in a solution of sól kamienna (rock salt), woda (water), czosnek (garlic), koper (dill), and liść chrzanu (horseradish leaf), sometimes with the addition of liście wiśni (cherry leaves) or gorczyca (mustard seeds) to enhance flavor and texture.

These cucumbers are typically packed into large słoje (jars) or kamionkowe garnki (stoneware crocks) and left to ferment at room temperature for several days or weeks, depending on the desired sharpness. The result is a ogórek twardy i kwaśny (firm and sour cucumber) that holds a central role in Polish meals. Whether served alongside schabowy (breaded pork cutlet), kanapki z pasztetem (sandwiches with pâté), or śledź w oleju (herring in oil), the ogórek kiszony provides contrast, zing, and a kind of culinary punctuation mark.

But the pickle’s significance goes beyond the plate. In Polish homes, especially in the countryside, the annual kiszenie ogórków (cucumber pickling) ritual is a late summer tradition, passed from babcia do wnuczki (grandmother to granddaughter), involving family members gathering in the kitchen or backyard to prepare dozens of jars for winter. The satisfaction of opening a jar of homemade pickles in the depths of February, tasting the sun and soil of July, is a sensory act of time travel and preservation. During imieniny, grillowanie (barbecues), or casual dinners, a dish of ogórki kiszone is never far from the table, often accompanied by wódka (vodka), with the cucumber serving as a beloved zakąska (snack between shots).

The cultural reverence for ogórek kiszony even extends to literature, songs, and humor. Children grow up singing about them, and adults joke that no true Pole can live without a pickle. Regional festivals like the Święto Ogórka in Krzeszów celebrate the pickle with competitions, tastings, and even cucumber-themed fashion. In a globalized era of processed condiments, the humble ogórek kiszony stands as a crunchy monument to simplicity, nature, and ancestral wisdom. With each bite, it offers not only flavor but connection—to land, to family, and to a Poland that values the power of the humble jar to hold memory, patience, and soul.

OPŁATEK

OPŁATEK (Christmas wafer) is one of the most touching and sacred elements of Polish holiday tradition, a thin, unleavened sheet of white chleb pszeniczny (wheat bread) that carries far more than taste—it holds błogosławieństwo (blessing), pojednanie (reconciliation), and rodzinne ciepło (family warmth). Typically embossed with religious scenes like the Narodzenie Pańskie (Nativity), the opłatek is shared during Wigilia (Christmas Eve), the most significant evening in the Polish liturgical calendar, when families gather for the wieczerza wigilijna (Christmas Eve supper), a ritual meal steeped in symbolism and restraint.

Before a single dish is tasted, the eldest member of the household distributes pieces of the opłatek, and each person takes turns breaking a fragment from another’s piece while exchanging heartfelt życzenia świąteczne (holiday wishes). These whispered wishes—often personal, sincere, and at times emotional—may include hopes for zdrowie (health), szczęście (happiness), miłość (love), or spełnienie marzeń (dreams fulfilled). It is a moment of duchowa bliskość (spiritual closeness) when grudges soften, silences are broken, and generations connect through a ritual that has remained unchanged for centuries. In this fragile gesture of breaking and sharing, the opłatek becomes a physical and symbolic act of dzielenie się sobą (sharing oneself).

The origins of the opłatek lie in the monastyczna tradycja (monastic tradition) of early Christian Europe, but in Poland, it evolved into a uniquely cherished custom, spreading from noble courts to humble cottages, across cities and villages. Its reach extended even further through the Polish diaspora, where emigranci (emigrants) in the United States, Canada, Australia, or the UK continue to exchange opłatki by post, ensuring that even across great distances, the connection to family and homeland is preserved. In some regions, especially in Podhale and Lubelszczyzna, opłatki kolorowe (colored wafers) are also given to animals on Christmas Eve, recognizing them as part of the household and honoring the old legend that animals speak at midnight on this holy night.

In the weeks leading up to Boże Narodzenie (Christmas), opłatki are sold in churches, parish offices, and sklepy religijne (religious shops), often wrapped in fine paper and treated with great care. Though flavorless, their importance is immense—they are not meant to be delicious, but sacred. In every household, the moment of łamanie się opłatkiem (breaking the wafer) is a pause, a breath, a space carved out of the year's noise and movement, where people truly look at one another and speak from the heart. In a world too often rushed, divided, and disconnected, the opłatek endures as a silent yet powerful vessel of hope, unity, and the enduring Polish belief in the holiness of simple things.

PĄCZEK

PĄCZEK (Polish doughnut) is the sweet, golden centerpiece of one of Poland’s most beloved culinary celebrations—Tłusty Czwartek (Fat Thursday), the final Thursday before Lent begins. On this day, bakeries, cafés, and home kitchens overflow with freshly fried pączki (plural), round, plump pastries filled traditionally with konfitura różana (rose petal jam), though modern variations include budyń waniliowy (vanilla custard), czekolada (chocolate), or śliwka suszona (dried plum). The dough is enriched with żółtka (egg yolks), masło (butter), and spirytus (spirit), which not only adds depth of flavor but helps prevent excessive oil absorption during frying, resulting in that iconic złocista skórka (golden crust) and tender, fluffy interior.

A well-made pączek should have a visible jasna obwódka (light ring) around its middle—a sign that it was fried at the right temperature. Once cooled, the doughnut is dusted with cukier puder (powdered sugar) or drizzled with lukier cytrynowy (lemon glaze), and sometimes sprinkled with skórka pomarańczowa (candied orange peel) for extra texture and aroma. On Tłusty Czwartek, it’s considered not only a pleasure but almost a duty to eat at least one pączek—refusing is said to bring pech (bad luck) for the year. The queues outside famed cukiernie (pastry shops) in cities like Warszawa, Kraków, and Poznań begin before sunrise, with locals eager to get their hands on the freshest batch. Some ambitious eaters participate in informal challenges, consuming dozens in a day, all in good fun.

The tradition of pączki dates back to medieval times, when they were originally filled with słonina (pork fat) or mięso (meat) and served as a savory dish before Lent. Over time, the recipe evolved, and by the 18th century, thanks to French culinary influence and refined baking techniques, pączki słodkie (sweet doughnuts) had become popular, especially in noble households. Today, they are available year-round, but their consumption peaks dramatically during the karnawał (carnival season), particularly on Tłusty Czwartek, when Poland collectively indulges before the lean season of Wielki Post (Lent).

Though industrial versions exist, nothing rivals the homemade or artisanal pączek—a doughnut that’s more than a dessert. It’s a celebration of excess, of tradition, of shared joy. The sound of sizzling oil, the sweet aroma wafting through cold February air, the powdered fingers and jam-stained lips—all of it forms a sensory ritual that marks time, memory, and Polish identity. In every bite of a pączek, there is laughter, indulgence, and the warmth of a culture that knows how to balance reverence with revelry.

PALMA WIELKANOCNA

PALMA WIELKANOCNA (Easter palm) is a vibrant and symbolic creation at the heart of Polish Niedziela Palmowa (Palm Sunday) celebrations, marking the beginning of Wielki Tydzień (Holy Week) and the joyful anticipation of Wielkanoc (Easter). Despite its name, the palma wielkanocna is not made from traditional palm fronds—instead, it reflects Poland’s northern climate and deep folk traditions, crafted from dried trawy (grasses), kwiaty polne (wildflowers), gałązki wierzby (willow branches), and zielone bukszpany (green boxwood). The inclusion of bazie (pussy willows)—fuzzy grey buds that blossom in early spring—adds softness and seasonal symbolism, representing renewal, fertility, and the triumph of life over winter.

These palmy range from modest hand-held sizes to towering constructions reaching several meters in height, especially in regions like Lipy and Łyse in Kurpie, or in Małopolska, where villages compete in konkursy na najwyższą palmę (contests for the tallest palm). Made by families, school groups, or entire communities, these colorful creations often feature braided wstążki (ribbons), hand-cut papierowe kwiaty (paper flowers), and intricately arranged layers of plant material, transforming them into walking sculptures of folk artistry. On Palm Sunday, church courtyards fill with parishioners holding their palmy high, waiting for them to be poświęcone (blessed) during Mass in a ritual that merges Christian liturgy with pogańskie echa (pagan echoes) of spring awakening and nature worship.

Once blessed, the palma is taken home and placed behind święty obraz (a holy image), on a wall or near the door, believed to bring błogosławieństwo (blessing), ochrona przed burzami (protection against storms), and general dobrobyt (prosperity) throughout the year. Some families break off bits of the palm and bury them in fields or weave them into wiązanki ziół (herb bundles) used during summer processions. Others keep them intact until the following year’s Popielec (Ash Wednesday), when they are burned and the ashes used for the ceremonial imposition on foreheads.

The making of a palma wielkanocna is also a powerful przekaz międzypokoleniowy (intergenerational exchange), where grandparents teach children not only the techniques but the deeper meanings—respect for tradition, nature, and community. In contemporary Poland, workshops and warsztaty rękodzieła (craft workshops) help preserve and innovate the tradition, blending ancestral knowledge with modern creativity. The palma wielkanocna stands not only as a religious symbol, but as a radiant affirmation of Polish folk identity, rural craftsmanship, and the joyful resilience that bursts forth after every long winter. It is a bouquet of faith, heritage, and hope held high against the spring sky.

PIERNIK

PIERNIK (gingerbread) is one of Poland’s most beloved and aromatic confections, deeply tied to both festive tradition and historical identity, particularly in the city of Toruń, where pierniki toruńskie (Toruń gingerbreads) have been produced since the Middle Ages. Known for their rich flavor and intricate shapes, pierniki are made from a dense, spiced dough that typically includes miód (honey), przyprawy korzenne (warming spices) such as cinnamon, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg, along with mąka żytnia (rye flour) and sometimes chopped orzechy (nuts) or skórka pomarańczowa (candied orange peel). This fragrant mixture is often left to rest for weeks or even months in a process called leżakowanie (aging), allowing the ingredients to meld and deepen in flavor before baking.

What sets Polish piernik apart is not only its taste but its form. In Toruń, traditional molds are used to create elaborate figures and scenes—serca (hearts), anioły (angels), konie (horses), and herby miejskie (city crests), each stamped with ornate detail and baked to perfection. Some are glazed with lukier (icing), filled with powidła śliwkowe (plum preserves), or covered in czekolada (chocolate), while others are simply dusted with flour and wrapped in papier ozdobny (decorative paper), becoming both gifts and edible art. The oldest recipe for piernik toruński dates back to the 14th century and helped place Toruń on the map as a center of trade and craftsmanship. The city’s location along the Wisła (Vistula River) and its role in the Związek Hanzeatycki (Hanseatic League) allowed spices and honey to flow in from abroad, enriching local recipes and fueling a gingerbread industry that still thrives today.

During Boże Narodzenie (Christmas), pierniki are omnipresent—in homes, markets, and schools—often shaped into stars, trees, or bells, and decorated with colorful lukrowane wzory (icing patterns). Children and parents bake them together in an annual ritual of scent, laughter, and anticipation, stringing them into edible garlands or placing them on the choinka (Christmas tree) as fragrant ornaments. In addition to holiday treats, piernik dojrzewający (matured gingerbread cake) is a rich, layered dessert made weeks ahead of Christmas, filled with powidła and cream, and served in thick, satisfying slices.

Beyond the kitchen, piernik plays a role in Polish cultural memory. It appears in folk tales, literature, and songs, and is the star of the Muzeum Toruńskiego Piernika (Toruń Gingerbread Museum), where visitors can make their own and learn about its evolution. A bite of piernik is more than a taste—it’s a sensory journey through Poland’s history of trade, tradition, and the enduring sweetness of home. It is warmth made solid, a spiced echo of centuries past, lovingly preserved in dough.

PISANKA

PISANKA (decorated Easter egg) is one of the most exquisite and meaningful symbols in Polish folk tradition, embodying centuries of craftsmanship, spiritual renewal, and springtime celebration. Derived from the verb pisać (to write), the term pisanka originally referred not to writing with letters, but to the act of inscribing intricate patterns on an egg’s shell using wosk pszczeli (beeswax) and natural dyes. This ancient technique—called batikowa metoda zdobienia (batik method of decoration)—is still practiced today, with artists drawing fine designs on the shell before dyeing it in layers of color, then melting off the wax to reveal delicate, contrasting lines. The process requires cierpliwość (patience), precyzja (precision), and a steady hand, turning each pisanka into a miniature work of art.

Each region of Poland has its own characteristic style and terminology. In Podlasie and Mazowsze, you’ll find pisanki z woskiem (wax-resist eggs) with symmetrical geometric motifs, while in Opolszczyzna, the use of rytowanie (scratching technique) creates white designs on deeply dyed eggs, known as kraszanki. In Łemkowszczyzna and Huculszczyzna, traditional pisanki often feature intricate motywy roślinne (plant motifs), ptaki (birds), and słońca (suns), each symbol carrying layers of znaczenie magiczne (magical meaning), such as protection, fertility, or eternal life.

The pisanka plays a central role in the Easter season, especially in the preparation of the święconka (blessed basket), where decorated eggs are placed alongside chleb, sól, kiełbasa, and other symbolic foods, all taken to church on Wielka Sobota (Holy Saturday) for blessing. On Wielkanoc (Easter Sunday), these eggs are shared at the breakfast table, broken and exchanged with wishes of zdrowia (health), miłości (love), and radości (joy). The act of giving a pisanka is a gesture of friendship, reconciliation, and good will—especially powerful in rural communities, where neighbors might deliver them by hand, accompanied by handwoven serwetki (doilies) and spring greenery.

Today, pisanki continue to thrive as both sacred objects and artistic expressions. In schools, domy kultury (cultural centers), and muzea etnograficzne (ethnographic museums), children and adults alike learn the traditional techniques and the stories behind the symbols. Contemporary artists innovate with new materials and themes, yet the essence remains: the egg as a vessel of życie (life), odrodzenie (rebirth), and tożsamość narodowa (national identity). More than just decoration, the pisanka is a vibrant testament to the Polish spirit—resilient, imaginative, and beautifully rooted in the rhythms of faith, earth, and season.

POLONEZ

POLONEZ (polonaise) is a majestic and dignified dance that occupies a place of high honor in Poland’s cultural and historical imagination, serving as both an elegant social ritual and a symbol of national identity. Performed in metrum trójdzielne (triple meter), the polonez is a slow, processional dance distinguished by its gliding steps, subtle gestures, and ceremonial formations. Its origins lie in the rural chodzony (walking dance) of Polish peasants, but by the 17th century it had been adopted and refined by the szlachta (nobility), becoming a fixture at courtly events, royal receptions, and aristocratic weddings. Over time, the polonez evolved into a hallmark of Polish style, grace, and patriotism.

What defines the polonez is its intricate choreography and elevated mood. Couples, led by the host or the highest-ranking guest, parade around the room in sweeping arcs and serpentine paths, exchanging meaningful ukłony (bows), light skłony głowy (head tilts), and deliberate hand gestures that communicate respect and mutual awareness. The dance is less about technical virtuosity and more about postawa (carriage), godność (dignity), and harmonia w ruchu (harmony in movement). It opens not only formal balls but also studniówka (Polish prom night), where graduating students dance their first official polonez as a rite of passage into adulthood.

In music, the polonez became a genre of its own, reaching its artistic pinnacle in the works of Fryderyk Chopin, whose passionate Polonezy fortepianowe (piano polonaises) transformed this noble dance into a symbol of defiant Polishness. His famous Polonez As-dur op. 53 (Polonaise in A-flat major)—known as the “Heroic”—blends martial rhythm with sweeping lyricism, evoking the spirit of a nation longing for freedom. Other composers, including Michał Kleofas Ogiński and Henryk Wieniawski, also contributed to the genre, using the polonez as a musical vehicle for duma narodowa (national pride) and tęsknota za ojczyzną (longing for the homeland).

Beyond music and dance halls, the polonez permeates Polish visual culture and literature. It is immortalized in "Pan Tadeusz" by Adam Mickiewicz, where the opening polonez at Soplica’s manor encapsulates the values of old Poland—honor, unity, and ceremonial beauty. The imagery of the polonez—flowing gowns, ornate uniforms, candlelit halls—is evoked whenever Poles recall their golden age or stage events of historical importance.